JFK’s Commencement Address in Syracuse 60 yrs ago Resonates Still

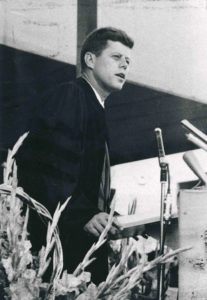

JFK at SU Commencement, 1957

reposted from SU News, written by Sean Kirst, May 12, 2017

As the Centennial of JFK’s Birth Nears, Recalling His Stirring Commencement Address in Syracuse

By 1957, a young United States senator from Massachusetts named John F. Kennedy already had a long working relationship with Ted Sorensen, who served at the time as his aide and counselor. Kennedy grew into greatness as an orator, and Sorensen gained famed as his speechwriter, as his quiet literary conscience.

The records at the John F. Kennedy Presidential Library & Museum in Massachusetts don’t reveal the collaborative genesis of a haunting and topical speech that Kennedy offered at the 1957 Syracuse University Commencement, 60 years ago in June.

But they do include a draft of the speech that Kennedy went over and edited, writing many notes or additions between the lines and in the margins. At one point, for instance, the speech referred to the “University of Syracuse.”

The soon-to-be president corrected it: Syracuse University.

These are fraught political times, filled with anger, recriminations and national division. The 100thanniversary of Kennedy’s birth is on May 29, rekindling a national discussion of his career and his achievements.

Still, the beauty of Kennedy’s 1957 address is the power and impartiality of the message, a theme that resonates today as much—if not more—than it did 60 years ago.

According to several accounts by Dick Case of the old Syracuse Newspapers—Case would go on to a long career as a columnist with the Syracuse Herald-Journal and Post-Standard—Kennedy stayed at the time at the Hotel Syracuse, now restored and reopened as the Marriott Syracuse Downtown. He was interviewed there by local journalists, who were well aware that his name was already being mentioned as a 1960 presidential hopeful.

Kennedy dodged questions about those aspirations. He was only 40. He said he was focused on being reelected as senator from Massachusetts.

The next day, on what Case called “a sunny Monday morning,” Kennedy gave his Commencement address to a crowd of about 6,000 at Archbold Stadium. He also offered a stylistic precursor to a choice he made at his inauguration, three years later: Kennedy would become known as “the man who killed the hat” because he chose to appear bare-headed before the nation.

In Syracuse, he declined to wear a mortar board when he spoke. He did wear one, however, when he accepted an honorary doctor of laws degree from Chancellor William P. Tolley, who described Kennedy as a war hero “who has always had the urge to move fast, and take the risks that come with speed.”

Kennedy’s speech was a thing of quiet beauty. He was a Democrat. Beyond a couple of gentle pokes, he essentially stayed away from any sparring about party affiliations. Instead, he started off by bringing his talk close to home: He told a story of how Elihu Root, a Nobel Peace Prize recipient with deep Upstate roots, once handled hecklers in Utica.

Then Kennedy went after his point. He was on a mission to remind the graduates of the nobility of elected office—even if everything in the culture seemed to be pushing the other way.

He told his listeners to be prepared for the way “great newspaper advertisements offer inducements (to be) chemists, engineers and electronic specialists.” He spoke of how the University was often “visited by prospective employers ranging from corporation vice presidents to professional football coaches,” a thought especially appropriate to a class that included graduating football legend Jim Brown.

“But few if any,” Kennedy said, “will urge you to become politicians.”

He noted how a Gallup poll claimed few mothers wanted their children to go into politics. He spoke of the way selfless political service went to the heart of the American experiment, yet of how the idea was often scorned or insulted by celebrities, intellectuals and other famous people. He recalled the time of Jefferson, when the notion of being a thinker and an artist was not exclusive to a dream of running for elected office.

“Politics, in short, has become one of our most neglected, our most abused and our most ignored professions,” Kennedy said. Far too often, he said, thoughtful people shun that arena and “consider their chief function to be that of the critic.”

Yet how will anything ever change, Kennedy wondered, if young Americans with talent, integrity and passion “lend your talents to merely discussing the issues and deploring their solutions”? In a world threatened by the shadow of nuclear war, he offered a simple challenge to the graduates:

“I ask you to decide, as Goethe put it, whether you will be a hammer—or an anvil.”

To Kennedy, the comparison was simple. To be an anvil equated to civic dormancy, to receiving and enduring the blows of a quickly changing society. He saw the hammer as equivalent to a person of action, willing to offer assistance as a citizen while accepting the risk and conflict inherent in public service.

Kennedy offered a summary of domestic and international worries that have only intensified today. He spoke of “pockets of chronic unemployment and sweatshop wages amidst the wonders of automation—monopoly, mental illness, race relations, taxation, international trade and, above all, the knotty complex problems of war and peace, of untangling the strife-ridden, hate-ridden Middle East, of preventing man’s destruction of man by nuclear war or even more awful to contemplate, by disabling through mutations generations yet unborn.”

To Kennedy there was only one clear response for his young audience:

“I would urge therefore that each of you, regardless of your chosen occupation, consider entering the field of politics at some point in your career,” Kennedy said. “It is not necessary that you be famous, that you effect radical changes in the government or that you are acclaimed by the government for your efforts. It is not even necessary that you be successful.

“I ask only that you offer to the political arena, and to the critical problems of our society which are decided therein, the benefit of the talents which society has helped to develop in you.”

Archbold Stadium is long gone. The University has gone through great physical change and expansion since that time. As for Kennedy, he would return to Syracuse and a passionate reception in 1960, during his successful campaign for president.

Three years later, in a moment that sent shock waves around the world, he was murdered by an assassin in Dallas. The impact of his life and his political legacy are still matters of study and debate by scholars and historians.

One thing seems indisputable about the young senator’s speech in Syracuse, about his thoughts on youth, responsibility and public service:

Sixty years later, as both hope and challenge, they stay true.

| M | T | W | T | F | S | S |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 |

| 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 13 | 14 |

| 15 | 16 | 17 | 18 | 19 | 20 | 21 |

| 22 | 23 | 24 | 25 | 26 | 27 | 28 |

| 29 | 30 | 31 | ||||

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- July 2020

- March 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- August 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- May 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- October 2013

- Academics (103)

- Admissions (94)

- Application Tips (22)

- Career and Alumni (72)

- Faculty and their Research (58)

- Featured (7)

- Financing Graduate School (37)

- SU News (58)

- Welcome (3)